Hydration Calculator for Oedema Management

Personalized Hydration Calculator

Get tailored water intake recommendations based on your health condition, activity level, and environment to help manage oedema.

Quick Takeaways

- Staying adequately hydrated helps keep the fluid balance in check, reducing the chance of swelling.

- Both over‑hydration and dehydration can worsen oedema; the goal is a balanced intake.

- Watch sodium, protein, and activity levels - they all interact with water in the body.

- Follow simple daily water‑drinking guidelines and adjust for health conditions.

- If swelling persists despite proper hydration, seek medical advice.

When you think about swelling, the first thing that comes to mind is often a bruise or an injury. Yet Oedema is a medical term for abnormal fluid accumulation in the body's tissues, and it can show up in the legs, arms, lungs, or even the face. What many people overlook is the close relationship between Hydration and the development or relief of oedema. This article walks you through why water matters, how the body manages fluids, and practical steps to keep swelling at bay.

What Exactly Is Oedema?

Oedema (also spelled edema) occurs when excess fluid leaks from blood vessels into surrounding tissue spaces. The fluid can be primarily water, but it often carries proteins, salts, and other solutes. Common triggers include heart failure, kidney disease, liver cirrhosis, and chronic venous insufficiency. The swelling is usually painless at first, but it can become tight, limit movement, and increase infection risk.

There are two broad types:

- Peripheral oedema: swelling in the lower legs, ankles, or feet - the classic “puffy” look.

- Pulmonary oedema: fluid in the lungs, a medical emergency that can cause shortness of breath.

Understanding the root cause is essential because treating the underlying condition often resolves the swelling.

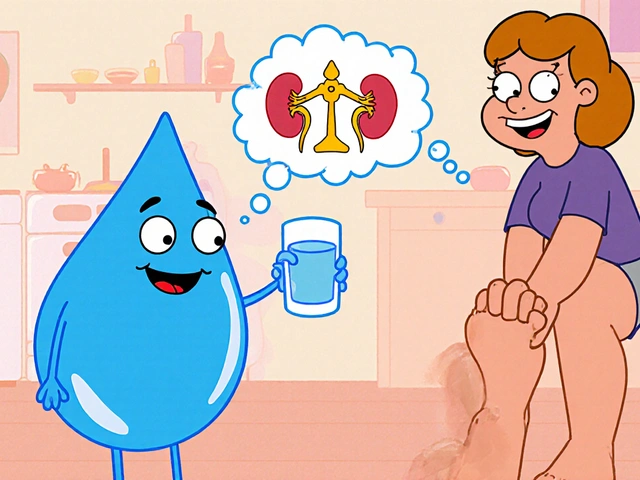

How Hydration Controls Fluid Balance

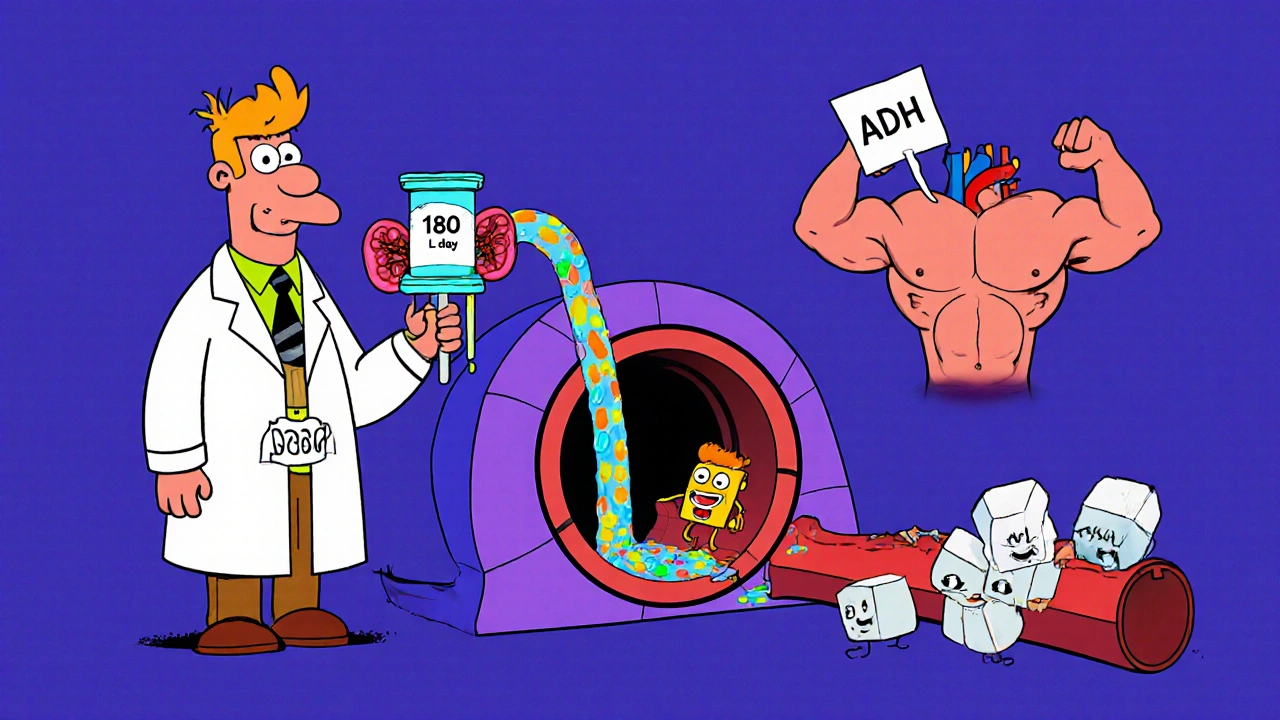

The human body is a finely tuned water‑management system. About 60 % of an adult's weight is water, distributed across cells, blood plasma, and interstitial spaces. Two key mechanisms keep this balance:

- Kidney filtration: The kidneys filter about 180 L of plasma each day, re‑absorbing needed water and excreting excess as urine.

- Hormonal regulation: Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and aldosterone adjust how much water the kidneys retain.

When you drink enough water, plasma volume stays stable, and the pressure inside blood vessels (capillary hydrostatic pressure) remains optimal. Too little water triggers the body to conserve fluid, raising ADH levels and causing the kidneys to retain sodium and water - a paradox that can actually promote oedema.

Conversely, drinking excess water without a proper electrolyte balance can dilute plasma sodium (hyponatremia), leading to fluid shifting into cells and worsening swelling. The sweet spot is a balanced intake that supports normal kidney function and keeps plasma osmolality around 285-295 mOsm/kg.

The Role of Sodium, Electrolytes, and Protein

Water doesn’t work in isolation. Sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and plasma proteins like albumin act as the “traffic controllers” that decide where fluid stays.

Key points:

- Sodium holds water in the bloodstream. High‑salt meals raise plasma sodium, pulling water out of cells and potentially raising capillary pressure.

- Electrolytes such as potassium counterbalance sodium and help prevent fluid from pooling.

- Albumin (a protein) creates an oncotic pressure that pulls water back into blood vessels. Low albumin, seen in liver disease or malnutrition, lets fluid leak into tissues.

Balancing these factors means you can’t just chug water and expect oedema to disappear. A well‑rounded diet, proper medication, and adequate hydration work together.

Daily Water‑Intake Guidelines Tailored to Oedema Risk

General recommendations (about 2.7 L for women and 3.7 L for men per the U.S. Institute of Medicine) are a good baseline. However, individual needs shift based on age, activity, climate, and health status.

Below is a quick reference that matches intake levels with common oedema‑related conditions.

| Condition | Suggested Daily Intake | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy adult | 2.5-3.0 L | Maintains normal plasma volume |

| Heart‑failure patients (moderate) | 1.5-2.0 L | Limits fluid overload while avoiding dehydration |

| Kidney‑disease (stage 3‑4) | 1.0-1.5 L | Reduces burden on impaired filtration |

| High‑altitude or hot‑climate workers | 3.0-4.0 L | Compensates for sweat‑induced losses |

Adjust the numbers up or down based on thirst, urine color (pale straw is ideal), and any doctor‑prescribed fluid limits.

Practical Steps to Keep Fluid Balance in Check

- Track your intake. Use a phone app or simple notebook. Aim for consistent sipping rather than big gulps.

- Watch the salt. Limit processed foods, fast‑food sauces, and canned soups. A 2‑gram (≈½ tsp) daily limit is a realistic target for most adults.

- Balance electrolytes. Include potassium‑rich foods (bananas, avocados, leafy greens) and, if needed, an electrolyte drink without added sugar.

- Move regularly. Light walking or calf‑pumping exercises help the Lymphatic system push excess fluid back toward the heart.

- Elevate swollen limbs. Raising legs above heart level for 15‑20 minutes several times a day reduces hydrostatic pressure.

- Check medications. Some diuretics encourage fluid loss, while certain antihypertensives can cause retention. Review them with your clinician.

- Mind the clothing. Tight socks or belts restrict venous return and worsen peripheral oedema.

When Hydration Alone Isn’t Enough

Even with perfect water habits, oedema may persist if a serious condition drives it. Here’s when to call a professional:

- Swelling appears suddenly and is accompanied by chest pain or shortness of breath - possible pulmonary oedema.

- Weight gain of more than 2 kg (4.4 lb) over a few days without a clear cause.

- Painful, tight skin that doesn’t soften with elevation.

- Persistent swelling despite low‑salt diet and fluid restriction.

Doctors may order blood tests (creatinine, albumin), imaging (ultrasound), or adjust medications (adding a stronger diuretic, for example). Early intervention keeps complications low.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

| Pitfall | Why It Happens | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Drinking too much water without electrolytes | Hyponatremia pulls water into cells | Add a pinch of sea salt or an electrolyte solution |

| Skipping fluids because of “water weight” fear | Dehydration triggers ADH, causing retention | Monitor urine color; aim for 6‑8 cups/day |

| Relying only on diuretics | Can cause electrolyte imbalance | Combine with diet, movement, and proper hydration |

| Ignoring underlying disease | Treating symptoms won’t stop progression | Regular check‑ups, blood panels, and imaging |

Bottom Line: Hydration Is a Cornerstone, Not a Cure‑All

The short answer? Keep your water intake steady, watch your salt, stay active, and treat any medical condition that’s driving the fluid shift. When you pair smart hydration with a balanced diet and lifestyle, the body’s natural pumps-kidneys, lymphatics, and heart-work together to keep swelling at bay.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can drinking more water reduce existing swelling?

Yes, if the swelling is caused by dehydration‑induced fluid retention. Proper water intake lowers ADH levels, allowing kidneys to excrete excess fluid. However, if the oedema stems from heart or kidney failure, water alone won’t fix it-medical treatment is needed.

Is it possible to drink too little water and still get oedema?

Absolutely. When the body senses low water volume, it holds onto sodium and water, raising blood pressure in the capillaries and pushing fluid into tissues. This paradoxical swelling is common in older adults who neglect thirst cues.

What’s a good daily sign that my hydration level is on point?

Pale‑yellow urine, regular bathroom trips (about 6-8 times a day), and feeling thirsty only after a few hours of no fluid are reliable indicators.

Should I limit fluids if I have peripheral oedema?

A modest restriction (often 1.5-2 L per day) is typical for heart‑failure patients, but the exact limit must come from a clinician. Cutting fluids too aggressively can backfire by raising ADH.

Do electrolyte drinks help with oedema?

When they contain balanced sodium and potassium, they can prevent hyponatremia that aggravates swelling. Avoid sugary sports drinks that add extra calories without benefit.

Tammy Sinz

October 22, 2025 AT 20:36Your deep dive into the physiology of oedema is impressive and shows a solid grasp of fluid dynamics.

I appreciate how you illuminate the paradox where both dehydration and over‑hydration can exacerbate swelling.

From a renal perspective, the glomerular filtration rate acts as the primary throttle controlling plasma volume.

When ADH spikes, the collecting ducts become less permeable, prompting the body to conserve water even if interstitial fluid is already abundant.

This hormonal feedback loop is why patients often report increased puffiness after a weekend of low fluid intake.

Conversely, hyponatremic states dilute plasma osmolality, driving water into intracellular compartments and manifesting as subtle peripheral oedema.

Your inclusion of oncotic pressure highlights the essential role of albumin in tethering fluid to the vascular compartment.

In liver cirrhosis, hypoalbuminemia collapses that oncotic gradient, allowing plasma to seep into the peritoneal cavity, which we term ascites.

The table you provided succinctly matches fluid targets to specific comorbidities, which is a valuable clinical tool.

However, the recommendation for a 2‑gram sodium ceiling could be further refined by considering individual dietary patterns.

For instance, patients consuming a Mediterranean diet may naturally stay below that threshold, whereas processed‑food heavy diets exceed it dramatically.

I also recommend integrating a measured potassium intake to counterbalance sodium's pressor effects.

A daily serving of leafy greens or a modest banana can supply the necessary electrolyte equilibrium without adding caloric load.

Moreover, light calf‑pumping exercises stimulate the venous return, essentially acting as a peripheral pump that mitigates hydrostatic pressure buildup.

From a therapeutic standpoint, pairing low‑dose thiazide diuretics with a modest fluid restriction often yields synergistic decongestion in heart‑failure patients.

Overall, your article not only educates but also equips readers with actionable steps, bridging the gap between pathophysiology and everyday self‑care.

John Connolly

October 27, 2025 AT 16:10Excellent synthesis of the renal and cardiovascular mechanisms, and the practical tips are spot‑on.

Maintaining a steady sip schedule rather than chugging large volumes helps keep ADH in check and supports consistent urine output.

For patients on diuretics, pairing the medication with a potassium‑rich snack can prevent hypokalemia, which often exacerbates fluid retention.

Lastly, reminding readers to monitor urine color offers an easy, everyday feedback loop for proper hydration.

Christa Wilson

November 1, 2025 AT 12:45Love how you broke it down – super clear and helpful! 😊

Sticking to those simple water‑tracking apps makes it way less intimidating.

Keep spreading the good vibes! 🌟

Sajeev Menon

November 6, 2025 AT 09:19Great points above! I think we can also add that many ppl forget to check their meds – some antihypertensives can actually trap fluid.

Also, a quick tip: set a reminder on your phone to stand up and do a calf‑pump every hour – it’s a simple way to boost lymphatic flow.

Don’t forget to keep an eye on your salt intake even if you’re drinking enough water, otherwise the body might still hold on to extra fluid.

Vin Alls

November 11, 2025 AT 05:53What a vibrant tapestry of science and self‑care you’ve woven! Your guide reads like a culinary recipe, blending the broth of renal physiology with the zest of electrolyte balance.

Imagine your bloodstream as a bustling kitchen: sodium is the seasoned chef, water the broth, and albumin the sous‑chef that keeps everything from spilling over.

Following your steps is like seasoning a dish just right – not too salty, not too watery, but perfectly balanced.

Michael Vandiver

November 16, 2025 AT 02:27Nice work! 👍 The table really helps visualise daily targets 🗒️ and the movement tips are spot on 🚶♂️💧

Suryadevan Vasu

November 20, 2025 AT 23:02Balancing fluids is a subtle dance between intake, excretion, and vascular pressures.

When any step falters, edema emerges as the body’s warning flag.

Adhering to tailored water goals restores harmony.

Emma Parker

November 25, 2025 AT 19:36Sounds good!